Convex set

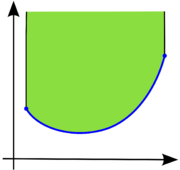

In Euclidean space, an object is convex if for every pair of points within the object, every point on the straight line segment that joins them is also within the object. For example, a solid cube is convex, but anything that is hollow or has a dent in it, for example, a crescent shape, is not convex.

Contents |

In Euclidean geometry

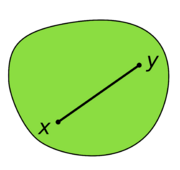

Let C be a set in a real or complex vector space. C is said to be convex if, for all x and y in C and all t in the interval [0,1], the point

- (1 − t ) x + t y

is in C. In other words, every point on the line segment connecting x and y is in C. This implies that a convex set in a real or complex topological vector space is path-connected, thus connected.

A set C is called absolutely convex if it is convex and balanced.

The convex subsets of R (the set of real numbers) are simply the intervals of R. Some examples of convex subsets of Euclidean 2-space are regular polygons and bodies of constant width. Some examples of convex subsets of Euclidean 3-space are the Archimedean solids and the Platonic solids. The Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra are examples of non-convex sets.

Properties

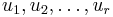

If  is a convex set, for any

is a convex set, for any  in

in  , and any nonnegative numbers

, and any nonnegative numbers  such that

such that  , then the vector

, then the vector  is in

is in  . A vector of this type is known as a convex combination of

. A vector of this type is known as a convex combination of  .

.

The intersection of any collection of convex sets is itself convex, so the convex subsets of a (real or complex) vector space form a complete lattice. This also means that any subset A of the vector space is contained within a smallest convex set (called the convex hull of A), namely the intersection of all convex sets containing A.

Closed convex sets can be characterised as the intersections of closed half-spaces (sets of point in space that lie on and to one side of a hyperplane). From what has just been said, it is clear that such intersections are convex, and they will also be closed sets. To prove the converse, i.e., every convex set may be represented as such intersection, one needs the supporting hyperplane theorem in the form that for a given closed convex set C and point P outside it, there is a closed half-space H that contains C and not P. The supporting hyperplane theorem is a special case of the Hahn–Banach theorem of functional analysis.

Star-convex sets

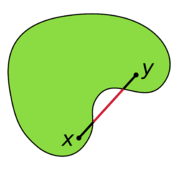

Let C be a set in a real or complex vector space. C is star convex if there exists an  in C such that the line segment from

in C such that the line segment from  to any point y in C is contained in C. Hence a non-empty convex set is always star-convex but a star-convex set is not always convex.

to any point y in C is contained in C. Hence a non-empty convex set is always star-convex but a star-convex set is not always convex.

Generalizations and extensions for convexity

The notion of convexity in the Euclidean space may be generalized by modifying the definition in some or other aspects. The common name "generalized convexity" is used, because the resulting objects retain certain properties of convex sets.

Orthogonal convexity

An example of generalized convexity is orthogonal convexity. [1]

A set S in the Euclidean space is called orthogonally convex or orthoconvex, if any segment parallel to any of the coordinate axes connecting two points of S lies totally within S. It is easy to prove that an intersection of any collection of orthoconvex sets is orthoconvex. Some other properties of convex sets are valid as well.

See "Orthogonal convex hull" for more.

Non-Euclidean geometry

The definition of a convex set and a convex hull extends naturally to non-Euclidean geometry by defining a geodesically convex set to be one that contains the geodesics joining any two points in the set.

Order topology

Convexity can be extended for a space  endowed with the order topology, using the total order

endowed with the order topology, using the total order  of the space.[2]

of the space.[2]

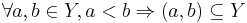

Let  . The subspace

. The subspace  is a convex set if for each pair of points

is a convex set if for each pair of points  such that

such that  , the interval

, the interval  is contained in

is contained in  . That is,

. That is,  is convex if and only if

is convex if and only if  .

.

Convexity spaces

The notion of convexity may be generalised to other objects, if certain properties of convexity are selected as axioms.

Given a set X, a convexity over X is a collection  of subsets of X satisfying the following axioms:[3]

of subsets of X satisfying the following axioms:[3]

- The empty set and X are in

- The intersection of any collection from

is in

is in  .

. - The union of a chain (with respect to the inclusion relation) of elements of

is in

is in  .

.

The elements of  are called convex sets and the pair (X,

are called convex sets and the pair (X,  ) is called a convexity space. For the ordinary convexity, the first two axioms hold, and the third one is trivial.

) is called a convexity space. For the ordinary convexity, the first two axioms hold, and the third one is trivial.

For an alternative definition of abstract convexity, more suited to discrete geometry, see the convex geometries associated with antimatroids.

See also

- Convex function

- Holomorphically convex hull

- Pseudoconvexity

- Convex metric space

- Concave set

References

- ↑ Rawlins G.J.E. and Wood D, "Ortho-convexity and its generalizations", in: Computational Morphology, 137-152. Elsevier, 1988.

- ↑ Munkres, James; Topology, Prentice Hall; 2nd edition (December 28, 1999). ISBN 0-13-181629-2.

- ↑ Soltan, Valeriu, Introduction to the Axiomatic Theory of Convexity, Ştiinţa, Chişinău, 1984 (in Russian).

External links

- Lectures on Convex Sets, notes by Niels Lauritzen, at Aarhus University, March 2010.